A classifier maps input examples (each a set of feature values) to class labels. Our task is to train a model on a set of examples with labels, and then assign the correct labels to new input examples.

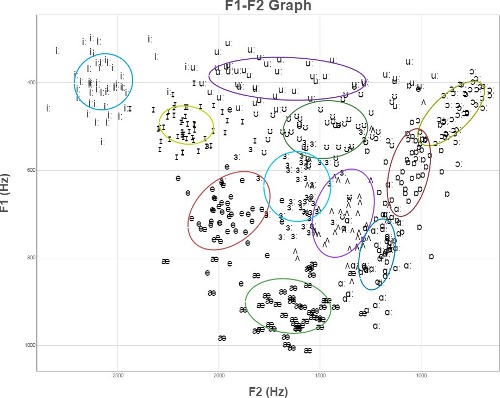

Here's a schematic representation of English vowels (from Wikipedia). From this, you might reasonable expect to experimental data to look like several tight clusters of points, well-separated. If that were true, then classification would be easy: model each cluster with a regeion of simple shape (e.g. ellipse), compare a new sample to these region, and pick the one that contains it.

However, experimental datapoints for these vowels (even after some normalization) actually look more like the following. If we can't improve the picture by clever normalization (sometimes possible), we need to use more robust methods of classification.

(These are the tirst two formants of English vowels by 50 British speakers, normalized by the mean and standard deviation of each speaker's productions. From the Experimental Phonetics course PALSG304 at UCL.)

We'll see four types of classifiers:

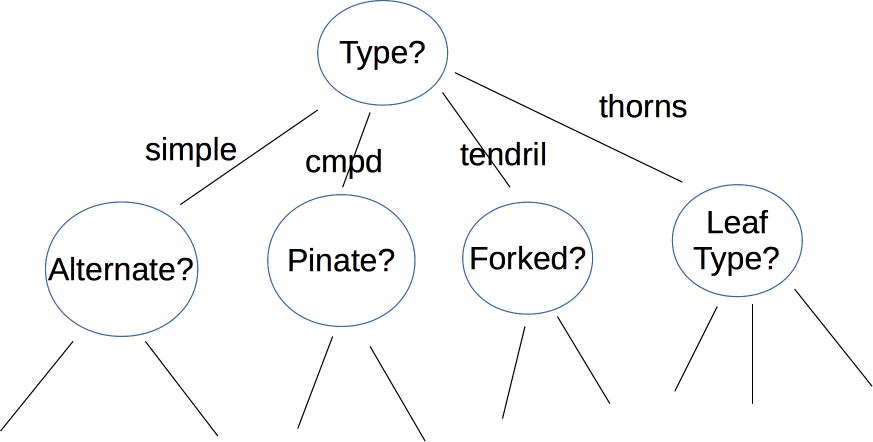

A decision tree makes its decision by asking a series of questions. For example, here is a a decision tree user interface for identifying vines (by Mara Cohen, Brandeis University). The features, in this case, are macroscopic properties of the vine that are easy for a human to determine, e.g. whether it has thorns. The top levels of this tree look like

Depending on the application, the nodes of the tree may ask yes/no questions, forced choice (e.g. simple vs. complex vs. tendril vs thorns), or set a threshold on a continuous space of values (e.g. is the tree below or above 6' tall?). The output label may be binary (e.g. is this poisonous?), from a small set (edible, other non-poisonous,poisonous), or from a large set (e.g. all vines found in Massachusetts).

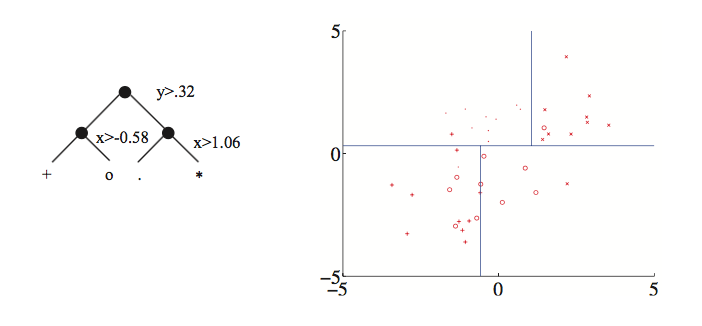

Here's an example of a tree created by thresholding two continuous variable values (from David Forsyth, Applied Machine Learning textbook, draft October 2018). Notice that the split on the second variable (x) is different for the two main branches.

Each node of the tree represents a pool of examples. The pool at a leaf node may contain examples that all have the same output type, e.g. if you have asked enough questions. Or the pool may represent several output values, in which case the algorithm returns the answer that's most popular in the pool. (Compare the bottom output values in the tree above to what's in the four regions of the 2D plot.) This may happen when the input feature values can't fully predict the output label (see the plot of English vowels above), or when the user has imposed a limit on the depth of the tree.

Decision tree algorithms can use a single deep tree, but these are difficult to construct (see the algorithm in Russell and Norvig) and prone to overfitting their training data. It is more effective to create a "forest" of shallow trees (bounded depth) and have these trees vote on the best label to return. These trees are created by choosing variables and possible split locations randomly.

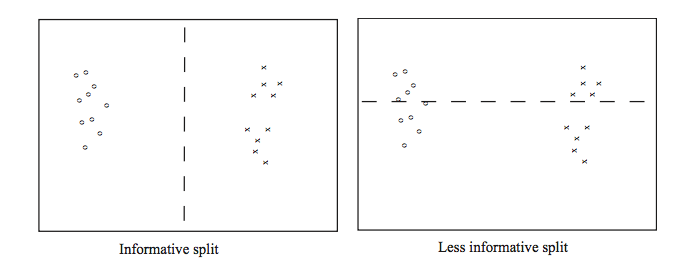

Even in a randomized context, some proposed splits are bad. For example, the righthand split leaves us with two half-size pools that are no more useful than the original big pool.

(From David Forsyth, Applied Machine Learning textbook, draft October 2018)

A good split must produce subpools that have lower entropy than the original pool. (See below on entropy.) Given two candidate splits (e.g. two thresholds for the same continuous variable), it's better to pick the one that produces lower entropy subpools.

Suppose that we are trying to compress English text, by translating each character into a string of bits. We'll get better compression if more frequent characters are given shorter bit strings. For example, the table below shows the frequencies and Huffman codes for letters in a toy example from Wikipedia.

| Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code | Char | Freq | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| space | 7 | 111 | a | 4 | 010 | e | 4 | 000 | ||||||||||||

| f | 3 | 1101 | h | 2 | 1010 | i | 2 | 1000 | m | 2 | 0111 | n | 2 | 0010 | s | 2 | 1011 | t | 2 | 0110 |

| l | 1 | 11001 | o | 1 | 00110 | p | 1 | 10011 | r | 1 | 11000 | u | 1 | 00111 | x | 1 | 10010 |

Suppose that we have a (finite) set of letter types S. Suppose that M is a finite list of letters from S, with each letter type (e.g. "e") possibly included more than once in M. Each letter type c has a probability P(c) (i.e. its fraction of the members of M). An optimal compression scheme would require \(\log(\frac{1}{P(c)}) \) bits in each code.

To understand why this is plausible, suppose that all the characters have the same probability. That means that our collection contains \(\frac{1}{P(c)} \) different characters. So we need \(\frac{1}{P(c)} \) different codes, therefore \(\log(\frac{1}{P(c)}) \) bits in each code.

The entropy of the list M is the average number of bits per character when we replace the letters in M with their codes. To compute this, we average the lengths of the codes, weighting the contribution of each letter c by its probability P(c). This give us

\( H(S) = \sum_{c \in S} P(c) \log(\frac{1}{P(c)}) \)

Recall that \(\log(\frac{1}{P(c)}) = -\log_2(P(c))\). Applying this, we get the standard form of the entropy definition.

\( H(S) = - \sum_{c \in S} P(c) \log(P(c)) \)

In practice, good compression schemes don't operate on individual characters and also they don't achieve this theoretical optimum bit rate. However, entropy is a very good way to measure the homogeneity of a collection of discrete values, such as the values in the decision tree pools.

For more information, look up Shannon's source coding theorem.

Another way to classify an input example is to find the most similar training example and copy its label. This "nearest neighbor" method is prone to overfitting, especially if the data is messy and so examples from different classes are somewhat intermixed. However, performance can be greatly improved by finding the k nearest neighbors for some small value of k (e.g. 5-10). To see this in pictures, look at Lana Lazebnik's slides (Fall 2018). A kd tree can be used to find efficiently find the nearest neighbors for an input example.

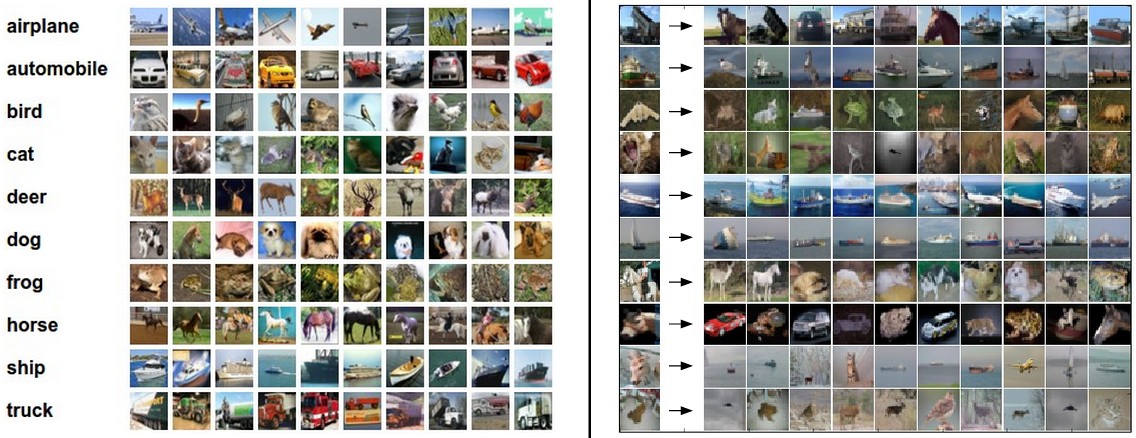

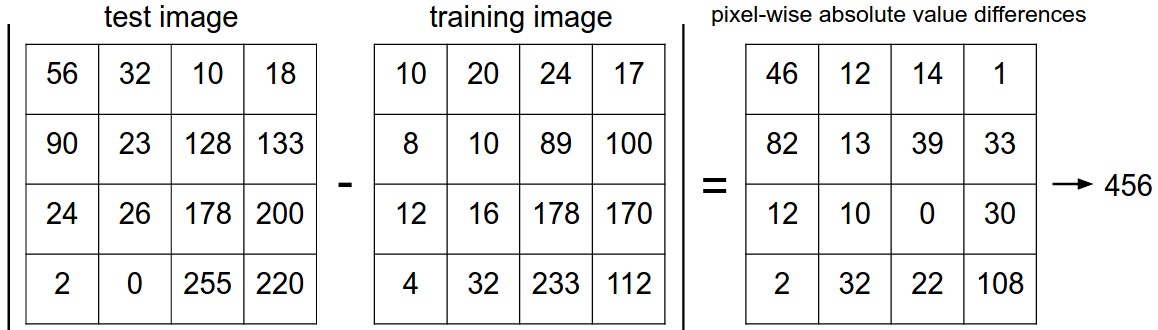

This method can be applied to somewhat more complex types of examples. Consider the CFAR-10 dataset below. Each image is 32 by 32, with 3 color values at each pixel. So we have 3072 feature values for each example. We can calculate the distance between two examples by subtracting corresponding feature values. The lower picture shows how this works for 4x4 grayscale images.

Above pictures are from Andrej Karpathy cs231n course notes (via Lana Lazebnik).

More precisely, there are two different simple ways to calculate the distance between two feature vectors (e.g. pixel values for two images) x and y.

As we saw with A* search for robot motion planning, the best choice depends on the details of your dataset. The L1 norm is less sensitive to outlier values. The L2 norm is continuous and differentiable, which can be handy for certain mathematical derivations.

Another approach to making a binary decision (e.g. a cat or not a cat) about an example X is to compute a function f(X) and compare its value against a threshold. This gives us both a decision and some indication how strongly we favor that decision. A simple model for f is a linear function of the input values. That is

\( f(X) = w_1 x_1 + \ldots + w_n x_n \)

Or, if you prefer to consistently test against the threshold zero, you can add an offset b:

\( f(X) = w_1 x_1 + \ldots + w_n x_n +b \)

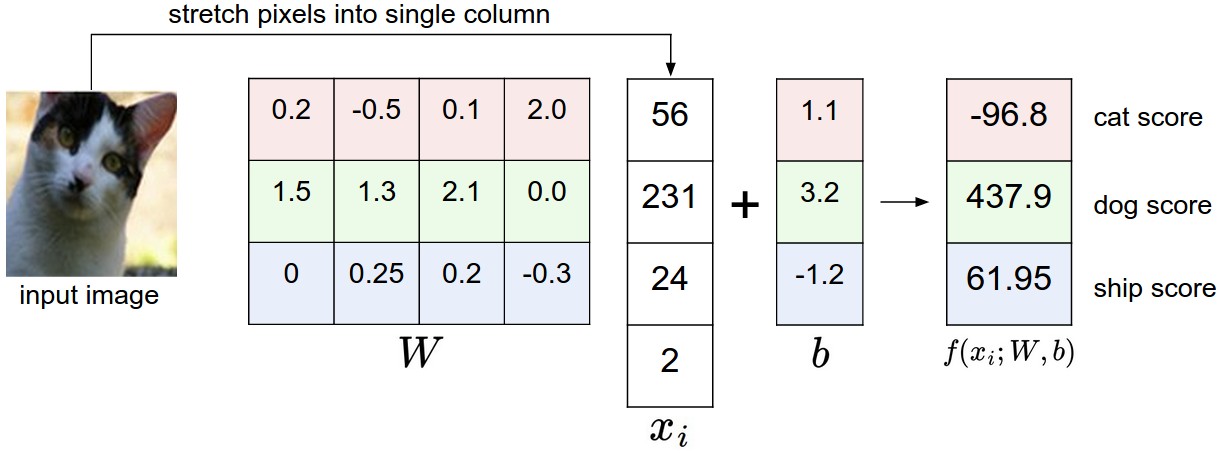

The figure below shows this idea used to create a multi-way classifier. Suppose (unrealistically) that our image has only four pixels. Pick a class (e.g. cat). The four pixel values \(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4 \) are multiplied by the weights for that class (e.g. the pink cells) to produce a score for that class. We then pick the class with the highest score.

(Picture from Andrej Karpathy cs231n course notes via Lana Lazebnik.)

In this toy example, the algorithm makes the wrong choice (dog). Clearly the weights \(w_i\) are key to success. Much of the discussion about such classifiers centers around how to learn good weights empirically from training data.