Rounding

Learning Objectives

- Measure the error in rounding numbers using the IEEE-754 floating point standard

- Predict the outcome of loss of significance in floating point arithmetic

Rounding Options in IEEE-754

Not all real numbers can be stored exactly as floating point numbers. Consider a real number in the normalized floating point form:

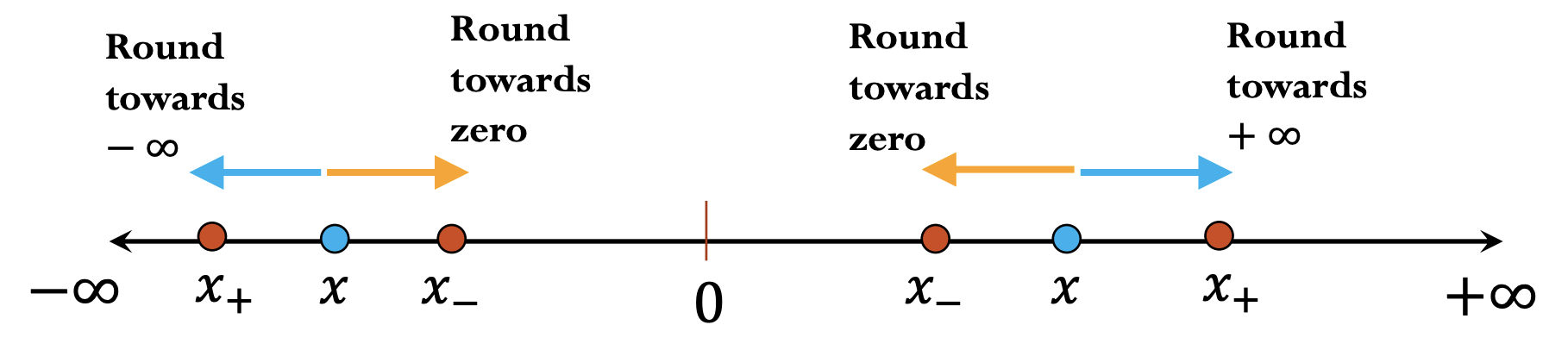

\[x = \pm 1.b_1 b_2 b_3 ... b_n ... \times 2^m\]where \(n\) is the number of bits in the significand and \(m\) is the exponent for a given floating point system. If \(x\) does not have an exact representation as a floating point number, it will be instead represented as either \(x_{-}\) or \(x_{+}\), the nearest two floating point numbers.

Without loss of generality, let us assume \(x\) is a positive number. In this case, we have:

\[x_{-} = 1.b_1 b_2 b_3 ... b_n \times 2^m\]and

\[x_{+} = 1.b_1 b_2 b_3 ... b_n \times 2^m + 0.\underbrace{000000...0001}_{n\text{ bits}} \times 2^m\]The process of replacing a real number \(x\) by a nearby machine number (either \(x_{-}\) or \(x_{+}\)) is called rounding, and the error involved is called roundoff error.

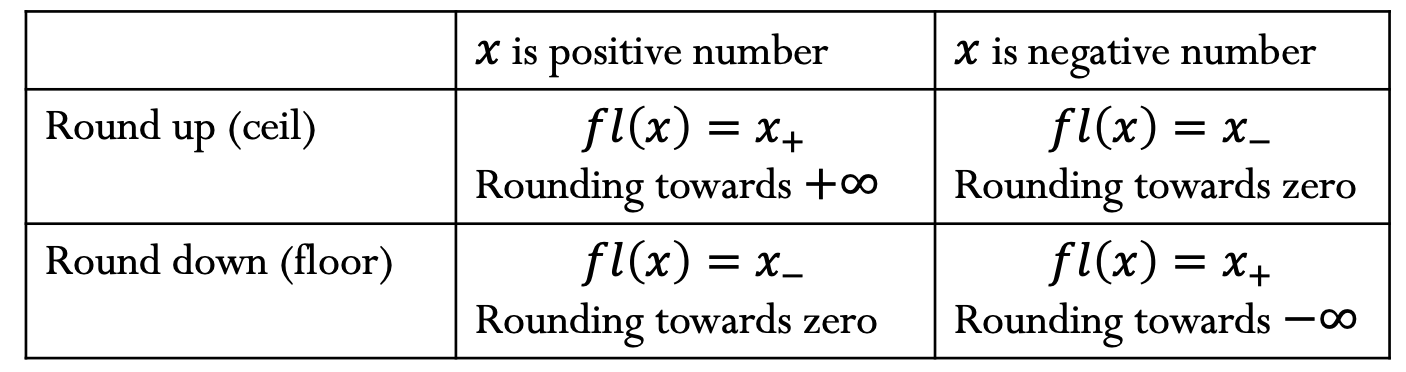

IEEE-754 doesn’t specify exactly how to round floating point numbers, but there are several different options:

- round towards zero

- round towards infinity

- round up

- round down

- round to the next nearest floating point number (round up or down, whatever is closer)

We will denote the floating point number as \(fl(x)\). The rounding rules above can be summarized in the table below:

Roundoff Errors

Note that the gap between two machine numbers is:

\[\vert x_{+} - x_{-} \vert = 0.\underbrace{000000...0001}_{n\text{ bits}} \times 2^m = \epsilon_m \times 2^m\]Hence we can use machine epsilon to bound the error in representing a real number as a machine number.

Absolute error:

\[\vert fl(x) - x \vert \le \vert x_{+} - x_{-} \vert = \epsilon_m \times 2^m\] \[\vert fl(x) - x \vert \le \epsilon_m \times 2^m\]Relative error:

\[\frac{ \vert fl(x) - x \vert }{ \vert x \vert } \le \frac{ \epsilon_m \times 2^m } { \vert x \vert }\] \[\frac{ \vert fl(x) - x \vert }{ \vert x \vert } \le \epsilon_m\]Floating Point Addition

Adding two floating point numbers is easy. The basic idea is:

- Bring both numbers to a common exponent

- Do grade-school addition from the front, until you run out of digits in your system

- Round the result

For example, in order to add \(a = (1.101)_2 \times 2^1\) and \(b = (1.001)_2 \times 2^{-1}\) in a floating point system with only 3 bits in the fractional part, this would look like:

You’ll notice that we added two numbers with 4 significant digits, and our result also has 4 significant digits. There is no loss of significant digits with floating point addition.

Floating Point Subtraction and Catastrophic Cancellation

Floating point subtraction works much the same was that addition does. However, problems occur when you subtract two numbers of similar magnitude.

For example, in order to subtract \(b = (1.1010)_2 \times 2^1\) from \(a = (1.1011)_2 \times 2^1\), this would look like:

When we normalize the result, we get \(1.???? \times 2^{-3}\). There is no data to indicate what the missing digits should be. Although the floating point number will be stored with 4 digits in the fractional, it will only be accurate to a single significant digit. This loss of significant digits is known as catastrophic cancellation.

Review Questions

- See this review link

ChangeLog

- 2020-04-28 Mariana Silva mfsilva@illinois.edu: started from content out of FP page; added new rounding text