Which of the following statements are true?

Answers:

Let \(f: \mathbb{Z}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(f(x,y) = 4x + 3y\)

Claim: f is onto

A function \(f:A\rightarrow B\) is onto if and only if

For every k in B, there is a value j in A such that f(j) = k.

So our specific function f is onto if and only if

For every integer k, there is a pair of integers \((x,y)\) such that f(x,y) = 4x + 3y = k.

On scratch paper

How to get 7 as output? input (1,1)

How to get 1 as output? input (1,-1) or (-2,3) or ....

How to get k as output? input (k, -k) or (-2k, 3k) or ...

For the proof, pick one way to find the pre-image of an output value k. Let's use (-2k, 3k).

Proof:

Let \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\).Consider \((-2k,4k) \in \mathbb{Z}^2\).

\(f(-2k,3k) = 4(-2k) + 3(3k) = -8k + 9k = k\). So \((-2k,3k)\) is a pre-image of k.

Since k was arbitrarily chosen, this means that every integer k has a pre-image. So f is onto.

Let \(g:\mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) be one-to-one.

Let \(f:\mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}^2\) such that \(f(x) = (g(x)|x|, |x|)\).

Prove that f is one-to-one.

A function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is one-to-one if

Proofs normally use the second form.

Slightly buggy proof:

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be integers. Suppose that \(f(x) = f(y)\).By the definition of \(f\), this means that \((g(x)|x|,|x|) = (g(y)|y|,|y|)\).

So \(g(x)|x| = g(y)|y|\) and \(|x| = |y|\).

So \(g(x)|x| = g(y)|x|\).

Dividing the this equation by \(|x|\), we get \(g(x) = g(y)\).

Since g is one-to-one, this implies that x = y, which is what we needed to prove.

Ooops: what happens if \(x=y=0\)?

Correct proof

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be integers. Suppose that \(f(x) = f(y)\).By the definition of \(f\), this means that \((g(x)|x|,|x|) = (g(y)|y|,|y|)\).

So \(g(x)|x| = g(y)|y|\) and \(|x| = |y|\).

There are two cases:

Case 1: \(|x| = 0\). So \(x = 0\). Since \(|x| = |y|\), \(y\) must also be zero. So \(x= y\).

Case 2: \(|x| \not = 0\). Since \(g(x)|x| = g(y)|y|\) and \(|x| = |y|\), we have \(g(x)|x| = g(y)|x|\).

Dividing this equation by \(|x|\), we get \(g(x) = g(y)\). Since g is onto, this implies that \(x = y\).

In both cases, \(x=y\), which is what we needed to prove.

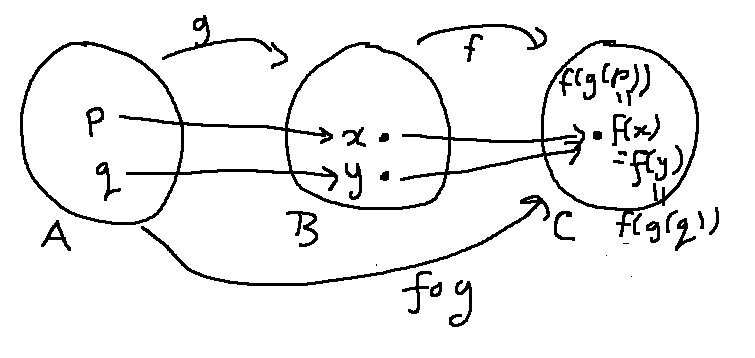

Claim: For any sets A, B, and C, and any functions \(g: A\rightarrow B\) and \(f: B\rightarrow C\), if \(f \circ g\) is one-to-one and g is onto, then f is one-to-one

What does this even mean and why do I think it's true?

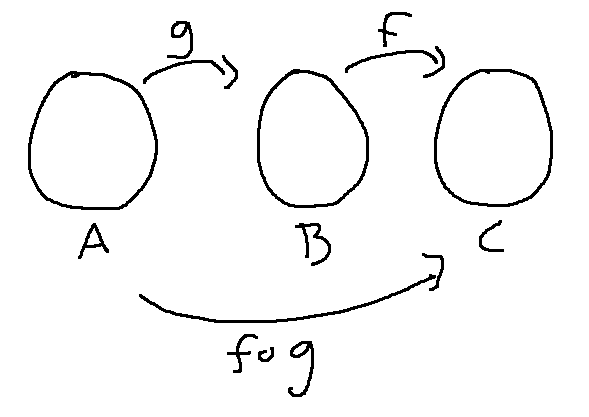

Recall: \((f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x)) \)

Bubble diagram for keeping track of what's going on:

Long ago, ten CS theory faculty played World of Warcraft and each one had an avatar. Jeff Erickson's avatar \(e_J\) might have been an elf with a purple braid. We can model this with two functions:

g:{CS theory faculty} \(\rightarrow\) {World of Warcraft avatars}

f: {World of Warcraft avatars} \(\rightarrow\) {hairstyles}

Let's say each theory faculty member had an avatar with a different hairstyle. Then \(f \circ g\) would be one-to-one.

But there were about 10 million World of Warcraft subscribers and only about 3000 hairstyles. So some avatars must have shared hairstyles. So f can't be one-to-one.

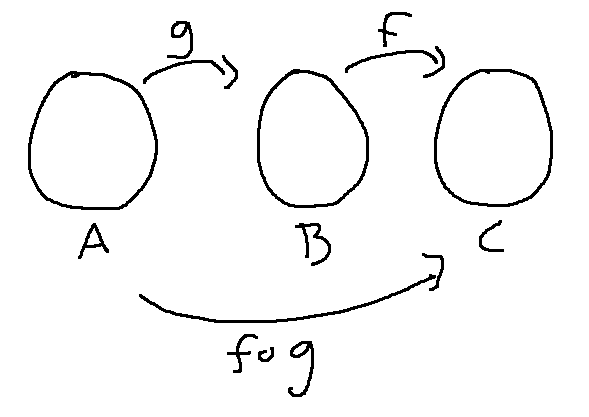

Here's the picture if Michelle Obama was also playing as an elf (\(e_M\)) with the same purple braid as Jeff's avatar.

![]()

So our claim won't work unless g's outputs cover all of B.

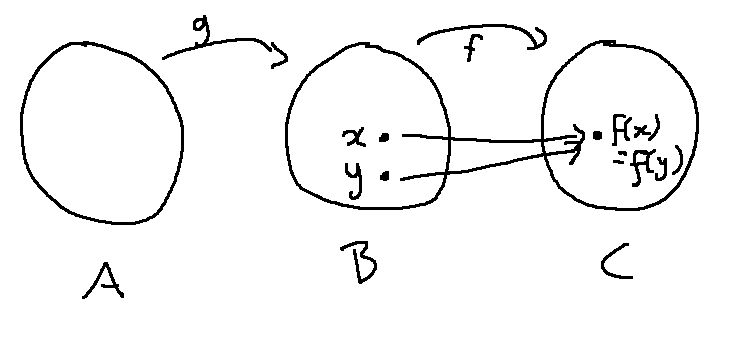

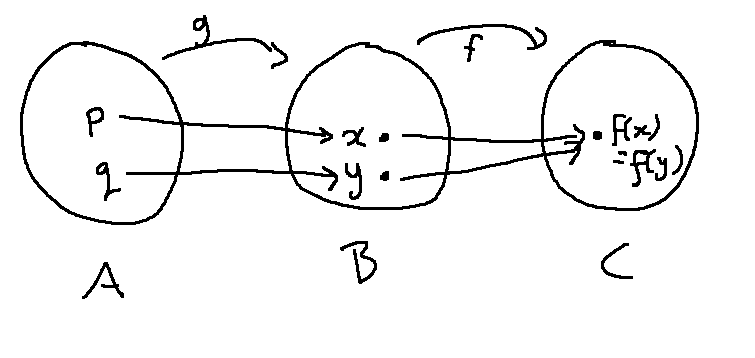

Pick \(x\) and \(y\) from B. Suppose \(f(x) = f(y)\). We need to show that \(x=y\).

\(g\) is onto. So we have pre-images for \(x\) and \(y\). \(g(p) = x\) and \(g(q) = y\).

Since \(f \circ g\) is one-to-one:

\((f \circ g)(p) = f(g(p)) = f(x)\)

\((f \circ g)(q) = f(g(q)) = f(y)\)

Since we know \(f(x)= f(y)\), we have \((f \circ g)(p) = (f \circ g)(q)\).

Since \((f \circ g)\) is one-to-one, this means \(p=q\) and therefore \(x=y\).

Proof:

Let \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) be sets and suppose that \(g: A\rightarrow B\) and \(f: B\rightarrow C\) are functions. Also suppose that \(f \circ g\) is one-to-one and g is onto.Let \(x\) and \(y\) be elements of \(B\). Suppose that \(f(x) = f(y)\). We need to show that \(x = y\).

Since \(g\) is onto, there are \(p\) and \(q\) in \(A\) such that \(g(p) = x\) and \(g(q) = y\).

\((f \circ g)(p) = f(g(p)) = f(x) = f(y) = f(g(q)) = (f \circ g)(q)\)

So \((f \circ g)(p) = (f \circ g)(q)\). Since \(f \circ g\) is one-to-one, this means that \(p=q\).

Since \(p=q\), \(g(p) = g(q)\). So \(x = g(p) = g(q) = y\). So \(x = y\).

We've shown that \(f(x) = f(y)\) implies that x=y. So f is one-to-one. \(\Box\)